*Note: I am very much not a doctor. When I use words like “anxiety” and “trauma” in this essay, I’m using them in their general, non-clinical sense, as a description of what I see on screen from the characters in these episodes, and not as part of any armchair diagnosis which I am eminently unqualified to make. I also write about the value of stories at difficult times in our lives, and while I believe in that value, I do want to stress that we should seek out help from real people, and especially from professionals, when we need it, and are in a position to safely do so.

Star Trek: The Next Generation – “Hollow Pursuits” (season 3, episode 21)

Written by Sally Caves; directed by Cliff Bole; first aired in 1990

We open in what appears to be Ten Forward, where engineer Reg Barclay nurses a drink as Guinan warns him not to start any trouble. He does indeed start trouble; when his supervisor, LaForge, reprimands him for drinking on the job, Barclay roughs up both Geordi and Riker, while a weirdly approving Troi watches on. Barclay is then called to the cargo bay, and exits what turns out to be the holodeck to report, late, for work. The real Riker and LaForge have had it with “Broccoli,” as they’ve nicknamed him behind his back, who is often late and distracted, and once he joins them in the cargo bay, we see a very different side of him than we did on the holodeck, soft-spoken and anxious. First Geordi, then Riker reprimand him for being late, and with no back-talk or fisticuffs this time, Barclay sets about trying, unsuccessfully, to figure out what’s gone wrong with an anti-gravity platform which has spilled some medical samples. Later, LaForge and Riker ask that Barclay be transferred off the Enterprise, but Picard refuses to treat him as a problem to be passed off on someone else, and orders Geordi to make a renewed effort to connect with him – and to cut it out with the cruel nickname, already (although Picard himself will later slip up on that front). On Picard’s orders and Guinan’s advice, Geordi does makes that effort, inviting Reg to contribute in engineering meetings about the spreading malfunctions on the ship, but Barclay continues to retreat into increasingly elaborate holodeck programs, including one in which LaForge, Data, and Picard are his Three Musketeers-style dueling opponents, and Troi and Crusher are his, uh, love interests. LaForge discovers this, and sympathizes with Barclay’s “holo-addiction,” even if he doesn’t quite grasp how difficult Reg’s social anxiety has made life for him. Geordi insists he needs Reg’s help “in the real world,” dealing with the increasingly severe malfunctions which have come to threaten the whole ship, and Reg successfully tracks the malfunctions to a material which leaked from the broken container in the cargo bay, and was spread through the ship by the engineering team. Crisis averted, we see Barclay saying goodbye to the bridge crew of the Enterprise … before telling the holodeck to end the program it’s running, and to erase all his programs (except one).

VS.

Star Trek: Deep Space Nine – “It’s Only a Paper Moon” (season 7, episode 10)

Teleplay by Ronald D. Moore; story by David Mack & John J. Ordover; directed by Anson Williams; first aired in 1998

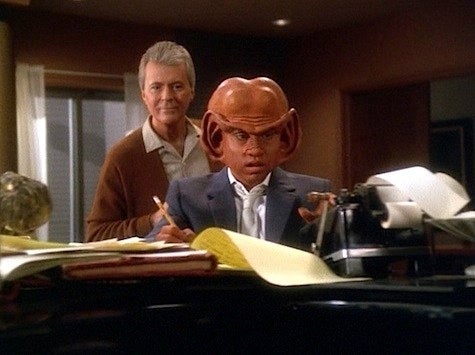

Nog’s family and friends gather to greet him as he returns home to the station, after extensive medical treatment and counselling following the loss of his leg in battle. They cheer his arrival, good-naturedly tease him, and invite him to a banquet in his honor. But Nog, worn down and limping on his new leg, just wants some rest. A later counselling session with Ezri doesn’t go so well, as he’s tired of doctors and counsellors telling him his replacement leg can’t possibly be as painful as he insists it is. His roommate Jake soon grows frustrated with Nog lying in bed all day and listening repeatedly to the old Earth standard “I’ll Be Seeing You,” which Nog remembers playing in the background as Dr. Bashir tended to his battle wounds. A withdrawn and still clearly traumatized Nog takes Jake’s advice, and heads to the holosuites where he loads Vic Fontaine’s Las Vegas casino program, and has Vic play “I’ll Be Seeing You” until his band runs out of different versions to play. Not wanting to leave the holosuite and return to his life, Nog asks to stay with Vic in his holographic hotel suite. Nog’s crewmates and family are concerned, but Ezri tentatively supports Nog spending his medical leave in the holosuite, and Vic offers to help wean Nog off the cane he shouldn’t need. We see Vic and Nog watching old Earth movies – in which Nog marvels at how little the protagonists are affected by their gunshot wounds – and generally spending time together, as Nog puts his Ferengi business smarts to use helping Vic run the casino and planning to build a new one, all still in the holo-program. Vic is enjoying the new experience of having his program running continuously, but Ezri reminds him that this isn’t about him, and he finally cuts Nog off, shutting down his own program and refusing to let Nog turn it back on. When Nog won’t stop tinkering with the holosuite, Vic reappears to confront him, and Nog finally opens up about the trauma he experienced in battle, and the paralyzing fear of his own mortality it left him with. Vic insists that staying in the holosuite would be an escape from life, not from death, and Nog finally emerges from the holosuite, telling his family that he’s not alright … but he will be. Some time later, back in uniform and seeming more like himself, Nog returns to thank Vic, and to tell him that he’s arranged for his program to be left running “26 hours a day,” so that Vic, too, can have a life of his own.

“It’s Only a Paper Moon” has long been one of my go-to re-watch episodes of Deep Space Nine, and of Star Trek, period. It’s a bit heavy for casual, sick-day viewing, maybe, but it’s the sort of episode I watch when I’ve had a hard day. An episode for when I need to be … well, not cheered up, exactly. Let’s say reassured: reassured that there’s more kindness than cruelty in the world; that most people want to help those who need it, even if they’re not sure how; and that, with help, we can get through bad times and emerge on the other side feeling, if not alright, then at least on the road to alright. It seems carefully, deliberately designed to be that kind of an episode, no matter that it was made before the days of video streaming, when its creators probably weren’t assuming that anyone actually would watch these episodes repeatedly, on demand. Yes, “It’s Only a Paper Moon” is heavy, and has only gotten heavier, accidentally but unavoidably, since the still-recent death of its standout star, Aron Eisenberg, in late 2019. But it juxtaposes that heaviness with a comfortable, disarming silliness that feels very specific to Deep Space Nine, even if it’s made possible, in this case, by an idea DS9 inherited from The Next Generation: the holodeck. This super-advanced simulation technology was one of the first 24th-century inventions The Next Generation teased us with in its very first episode, and while episodes like “The Big Goodbye,” “Elementary, Dear Data,” and “A Fistful of Datas” use the holodeck in some pretty memorable ways, I’d argue that the third season’s “Hollow Pursuits” is probably TNG’s most significant use of this technology, and the holodeck-centered episode that comes closest to the emotional realism of “It’s Only a Paper Moon.”

“Hollow Pursuits” was probably always going to be significant, due to its introduction of Reg Barclay, who would go on to be not just a recurring character on TNG, but one of very few characters to make multiple appearances in more than one series of Star Trek, playing a pretty important part in the ongoing central storyline of Voyager as well. And Barclay himself is significant as more than just a piece of trivia. Star Trek had always been about the best and brightest of future humanity exploring the final frontier, and it had tended to be relatively inclusive in its vision of what those best and brightest would look like. But Barclay was arguably the franchise’s first character to seriously challenge common assumptions about how the best and brightest of humanity might act, the first recurring crew member of a Starfleet ship who didn’t fit neatly into contemporary stereotypes of how heroes, or even just professionals, comport themselves. We’d seen awkward social interactions from Spock and Data before Barclay, of course, but those were non-human characters whose awkwardness spoke to the challenges of intercultural communication, and who still exhibited a traditionally heroic confidence in their own competence. Barclay is just human, and his social struggles are also very human, though they’re the kind of human struggles that don’t typically get the heroic treatment on TV. As a result, “Hollow Pursuits” is a rare example from TNG of the holodeck not going berserk and trying to kill everyone, but being used by Barclay as many of us might use it, if it were real: as a temporary relief from those struggles, however ineffective or counter-productive that relief might turn out to be. As I wrote before about the holodeck:

I can imagine how some TV writers might respond to my criticism of the harmless-simulation-turned-death-trap trope: of course things go wrong when characters use the holodeck, because if things went right, there’d be no story. And sure, this is true, to an extent. I just think it’s much more interesting when the things that go wrong with a fictional technology actually reflect the interesting implications of that specific technology, and not a simplistic, generalized fear of technology “going too far.”

And this is exactly what “Hollow Pursuits” does to set itself apart from TNG’s other holodeck misadventures: it creates conflict by imagining what might go wrong with this technology when it is working properly. Barclay isn’t trapped on the holodeck by some convenient malfunction. He just spends so much time there that it interferes with his sleep and work schedules, aggravating the social anxiety that has him spending so much time there in the first place. This is a relatively mundane problem, by Star Trek’s galaxy-spanning standards; hence the B-story, in which the fate of the Enterprise is at stake. But it’s a very human problem, which is precisely what makes it so relatable, and has allowed the episode to age pretty well, I think, as we’ve watched the Internet evolve into such a simultaneous blessing and curse – a wonderfully useful thing that can so easily eat up so much more of our time and emotional energy than we mean for it to, and can send us down some unhealthy rabbit holes if we’re not careful.

This double-edged aspect of new technologies, a topic of so much debate and so many hot takes in the real world, is conspicuously absent throughout much of The Next Generation, at least when it comes to the Federation’s own advanced tech. The series is basically built on the idea that, ever since humanity moved on from the “post-atomic horror” of the 21st century, technological and societal progress have gone hand in hand, one leading unproblematically to the other, with the Enterprise itself, a moving paradise in space, serving as the ultimate example of this. The concept of “holo-addiction,” introduced here in “Hollow Pursuits,” is one of the few times I can remember TNG explicitly acknowledging an inherent downside to any of its miraculous technology. Even here, LaForge’s comment that Barclay will be able to “write the book” on such an addiction implies that this is a relatively new and uncommon problem, which I find very hard to believe (especially considering Geordi’s own, mentioned history of creepy holodeck use, from the episode “Booby Trap”). And while “It’s Only a Paper Moon” takes the double-edged implications of holodeck technology even further, Nog’s family and friends still react to his own escape into the holodeck as if it were shocking and unheard of, much as Barclay’s crewmates do when they realize he’s been incorporating them into his programs without their consent, when these are exactly the sorts of things we’d immediately see heated debates about if the holodeck were invented today (not to mention the inevitable click-bait op-eds, like “Are You Spending Too Much Time on the Holodeck?” or “How Millennial Holodeck Use is Killing the _______ Industry”). Even so, these episodes recognize that technology doesn’t arrive out of nowhere, to help or hurt humanity with a mind of its own; its existence, its uses, and its effects tell as human a story as either of these episodes.

And the human stories told by these episodes are, again, not the sort of stories Trek had traditionally told particularly well before Deep Space Nine came along. While The Next Generation’s optimism for our future can be comforting, I do worry that it can inadvertently erase elements of human experience that ought to be better understood in an optimistic utopia, not thrown out with the post-atomic bathwater. As a kid growing up watching The Original Series and The Next Generation, I always liked to think I saw myself in Spock and Data, those noble outsiders. But looking back now, with a bit more self-awareness, I’d say that Barclay was probably the first character in all of Star Trek that I really saw myself in, warts and all; someone whose difficulties fitting into the world would likely be described, by others, not as noble and heroic, but embarrassing and inconvenient. Maybe this is why younger me found Barclay hard to watch, and why, to this day, the sight of anyone, real or fictional, embarrassing themselves on TV makes me as physically uncomfortable as any amount of on-screen blood and guts (and this isn’t an exaggeration; I literally cringe and avert my eyes during Michael Scott’s most embarrassing moments in The Office, the way others do during horror movies). But setting that discomfort aside as much as possible, I can appreciate the character of Barclay today in a way I couldn’t back then, and for a series whose treatment of mental and emotional health can sometimes seem a bit dated, TNG actually handles Barclay’s social anxiety quite gracefully in “Hollow Pursuits.” This conversation between Reg and Geordi in Ten Forward, for example, feels very true to the real-world difficulty of describing feelings and experiences like Barclay’s to those who haven’t felt or experienced them, even someone as genuinely well-meaning as LaForge seems to be by this point in the episode:

Barclay: It’s, it’s … I … when I’m in there, I’m just more comfortable. You don’t know what a struggle this has been for me, Commander.

LaForge: I’d like to help, if I can.

B: Being afraid all the time, of forgetting somebody’s name, not knowing what to do with your hands. I mean, I’m the guy who writes down things to remember to say when there’s a party. And then when he finally gets there, he winds up alone in the corner, trying to look comfortable examining a potted plant.

L: You’re just shy, Barclay.

B: “Just shy.” Sounds like nothing serious, doesn’t it? You can’t know.

Where I feel a little less sympathetic towards Barclay, if I’m being honest, is in his tendency towards power fantasies in his holo-programs of choice – his insistence on playing a macho-manly-type so categorically different from who he actually is. That isn’t a critique of the episode itself, necessarily; after all, if triple-A video games are any indication, these sorts of power fantasies are exactly how many of us – and let’s face it, many of my fellow men, in particular – would use the holodeck if we could. But this is a striking difference between “Hollow Pursuits” and “It’s Only a Paper Moon.” While Nog, like Barclay, looks to the holosuite for relief from what’s bothering him, his own virtual refuge is notably not a power fantasy. Yes, he uses his accounting skills to boost Vic’s business, but this isn’t anything he wouldn’t be capable of outside the holosuite, presumably. And given that he’s there because of injuries suffered in battle with the Dominion, we might expect him to pick a program that could give him some virtual payback for his lost leg – a first-person shooter, say, in which he could gun down simulated Jem’Hadar soldiers. But instead he chooses Vic’s Place, the perfect opposite of a battleground. He does become unacceptably violent with Jake, of course, and unacceptably cruel towards Kesha, Jake’s date, but only after Kesha calls him a war hero; he’s violently rejecting power over life and death, not reclaiming it.

And that, I think, is a big part of what makes “It’s Only a Paper Moon” so rewatchable for me, so reassuring at the end of a bad day, in spite of how heavy it gets. The episode is, in effect, a dramatization of exactly that – of escaping your troubles in a good piece of fiction, only to have that fiction confront you with those troubles in unexpected ways, if you’re willing to hear it. The word “escapism” is often used simplistically, to dismiss forms of fiction we don’t like or can’t relate to – or conversely, to defend fiction we do like from any sort of critical analysis that might change how we feel about it. But “Hollow Pursuits” and “It’s Only a Paper Moon” give us a relatively nuanced look at the bad and the good inherent in escapism. In “Hollow Pursuits,” I don’t think Barclay’s holodeck escapism is automatically written off as bad just because of which fantasies, exactly, he’s escaping into (although, again, there’s certainly a discussion to be had about the ethics of simulating real people); we’re shown that this particular brand of escapism is harmful to him, in that it gives the illusion of making his life easier, while actually making his life outside the holodeck more difficult.

“It’s Only a Paper Moon,” on the other hand, shows us that escapism isn’t all bad. Yes, Nog’s insistence on staying with holographic Vic strains his relationship with friends and family, but as we see from the argument with Jake which sends Nog to the holosuite in the first place, those relationships probably would have been strained anyway, as Nog struggled to process the feelings brought up by his injury and his loss. Nog feels changed by his experiences, feels fundamentally unable to see the world the way he used to, and however good their intentions, the attempts by Jake and Ezri and everyone else to treat him like his old self – to see him go back to his old self – just make him feel more out of place in the real world. Vic’s Place, by virtue of not being “real,” starts out as a refuge from his feelings, but ultimately it offers him a way to process those feelings that he couldn’t find elsewhere. In Vic’s Place, he’s just a patron, not a traumatized Starfleet war hero, and his newfound friendship with Vic places no pressure on him to be who he was before. And even when Vic finally shows some tough love, he can do so from a perspective Nog can relate to – that of someone whose life has been fundamentally changed by the time he’s spent with Nog, his program running non-stop in a way it never had before, giving him essentially a different life than he had before. This is the upside to escapism: by giving them an audience, we give these characters an opportunity to “live,” and they, in turn, have the chance to offer us a perspective, while we’re relatively relaxed and receptive, which we may not be getting, or may not be ready to hear, from the real people in our lives.

Deep Space Nine is especially well-suited to pulling off the precise blend of silliness and seriousness that makes such disarming moments possible, and there may be no better example of that balancing act than DS9’s Ferengi characters in general, and especially Nog himself. He was introduced to the series largely as comic relief, a foil for young Jake Sisko in light-hearted diversions like their quest to sell off some self-sealing stem bolts. And he could very easily have remained little more than a joke as the series continued; a joke in poor taste is what the Ferengi mostly were (whether they were meant to be or not) throughout the run of The Next Generation, the series that introduced them, and they would continue to be mostly a joke in their later appearances in Voyager and Enterprise. Only DS9 ever managed (or bothered) to give the Ferengi any real depth or complexity, and while this is partly the result of fleshing out Ferengi culture and customs, I think the lion’s share of the credit has to go to the actors who played the series’ recurring Ferengi characters. Armin Shimerman, as Quark, can be seen doing this work right from his very first appearance, in “Emissary”; as soon as he opens his mouth, we can immediately tell that his portrayal of the Ferengi will be more nuanced and humane than any we’d gotten to that point, and this lays the groundwork for Max Grodenchik, as Rom, and Aron Eisenberg, as Nog, to give similar depth to their own characters as the series goes on. Where the Ferengi began as the poster children for Star Trek’s troubling tendency toward simplistic, monolithic visions of alien societies, Quark, Rom, and especially Nog end up as the ultimate realization of Trek’s best impulse: its insistence that anyone can better themselves, that anyone can be better understood with time and effort … that everyone is, essentially, “human,” with all the good, bad, and everything else that entails.

And “It’s Only a Paper Moon” is, arguably, the culmination of this character arc for Nog, and the perfect showcase for the sweet, vulnerable humanity Aron Eisenberg lends him. When describing the character’s progress through the series, there’s a tendency to focus on his status as the first Ferengi in Starfleet, and for good reason. As mentioned above, Starfleet has always been emblematic of human progress, and the professionalism and diversity of its officers has always symbolized the height of human potential. The inclusion of Spock, Star Trek’s first alien, among this best and brightest of “humanity” was an obviously important move by The Original Series, one that set a tone for all the Trek that came after it. For Nog to be included among them as well, during wartime no less, carries all the weight of that well-established symbolism, amplified by the Ferengi’s reputation, in- and out-of-universe, as the last species one might expect to see represented in Starfleet. But the Nog we see in “It’s Only a Paper Moon” isn’t just Starfleet, or even just a heroic survivor of the horrors of war. He is those things, and he does represent the best and brightest of humanity, whatever his species … but he also represents just humanity, period.

Like Reg Barclay, if for different reasons, the Nog we see in “Paper Moon” doesn’t fit neatly into our expectations of how Starfleet officers, or the best and brightest of humanity in general, might act – how they might cope with challenges or hardship. No one on the station brushes off the trauma Nog has faced, just as no one who actually takes the time to get to know Barclay brushes off his anxieties in “Hollow Pursuits” (even if others do, like the somewhat uncharacteristically harsh Commander Riker). But these well-meaning friends, family members, and coworkers reflect our present-day society in their difficulty grasping that trauma and anxiety can be lasting conditions with lasting effects, and have to be processed and adjusted to over time, not immediately bounced back from. Nog is allowed, in “Paper Moon,” to be someone who can’t just immediately get “back to normal” once he has physically recovered, no matter how supportive everyone else is, and no matter how healthy he appears, outwardly, to them. How he feels is allowed to be inconvenient and confusing to them; to not conform to their expectations of what recovery looks like; to be beyond their frame of reference. How he processes those feelings is allowed to look unheroic, undignified, even ugly at times, to them and to us. Because his experiences are not about them, or us … which, paradoxically, is part of what makes this episode so relatable and reassuring for us, or at least for me. Because not only do the people already in his life stick by him as best they are able during his recovery, but it’s at this low point for Nog that he forms a new friendship with Vic, one so profound that it literally changes Vic’s life – changes the very nature of what Vic is – precisely because they’re each in a position to appreciate the other’s situation in a way that others can’t, as much as they may want to. Not everyone in the real world gets the support Nog does here, but this episode does what it can to remind us that our experiences matter, whether others understand them or not; that we matter, whether we can fit ourselves into others’ expectations for us or not.

And it’s to the great credit of James Darren as Vic Fontaine, Nicole de Boer as Counsellor Ezri Dax, and the late Aron Eisenberg as Nog, that they make this episode as fun to watch as it is powerful to think about. You don’t need me to sing Eisenberg’s praises, here: delving at all into his legacy in Trek fan spaces will unveil an endless amount of good will for this beautiful human being, and for the beautiful work he did in humanizing Nog. I’ll just say that that humanity is on full display here, as it is from Darren as the holographic Vic, and as much as Nog’s pain hits home, so do his joy and his enthusiasm and his resolve to keep living his life. This mixture of wacky holodeck hijinks and serious life stuff has no business working on screen, and it likely wouldn’t have worked in another series of Star Trek, or in many other series, period. But “It’s Only a Paper Moon” doesn’t just work, it resonates, because its lead performances resonate; they’re subtle when they need to be, tear-jerking when they need to be, and joyfully fun when they need to be. Nog’s cathartic speech near the episode’s end is a perfect emotional roller coaster, and his buddy-comedy bonding with Vic in 1960s Las Vegas is sheer, rewatchable fun. But I’ll leave you with this smaller, subtler moment which gets me every time, and pretty much sums up how I feel about this episode, as a subdued, exhausted Nog meets the upbeat Vic, and requests the song he can count on to make him feel better:

Vic: You’re Rom’s kid, right?

Nog: Right.

V: He’s really proud of you. He’s always in here bragging about his son, the soldier boy.

N: … Yeah.

V: What can I do for you?

N: I want to hear “I’ll Be Seeing You.”

V: Sure thing, kiddo. Any other requests?

N: No. Just “I’ll Be Seeing You.”

V: Sounds like a special tune.

N: It is. It helped me, once, when I was … unhappy.

V: What more can you ask from a song?

Great post. I love how you connected these two episodes whose tones are different but whose main idea is surprisingly similar, as you explained well.

And you’re right: It’s Only a Paper Moon is heavier now that poor Eisenberg left this planet. :–(

LikeLiked by 1 person